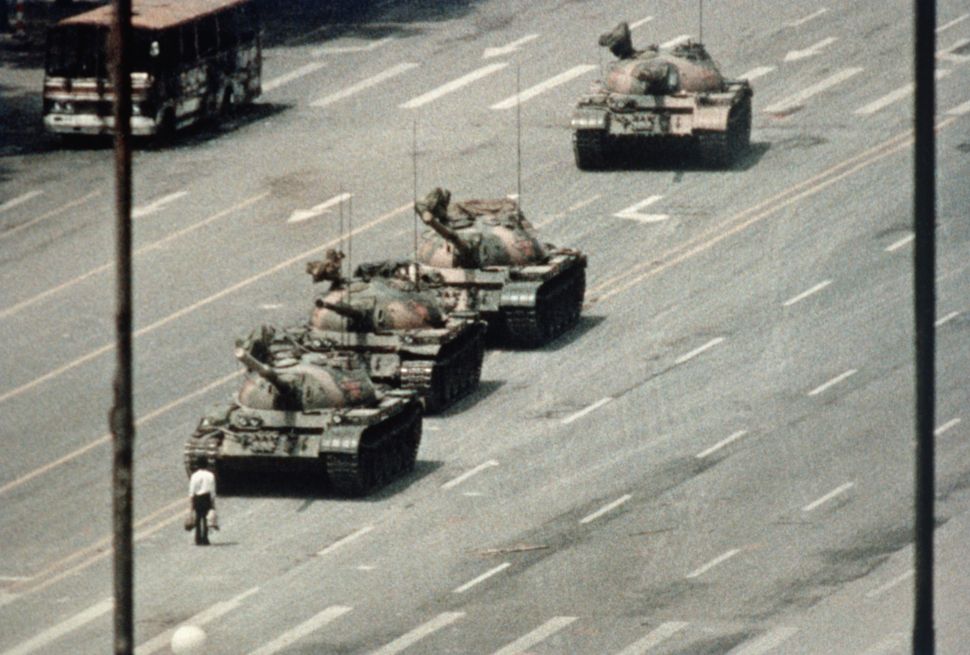

Thirty years ago, history was made when the Chinese Communist government slaughtered an estimated 10,000 student protesters. It launched CNN’s 24-hour news cycle. It ushered in an era of Chinese dictatorship and the centralization of power for authoritarians as opposed to one-party rule, with fealty to communism dominating the power a Chinese president can wield. And it helped make the political career of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

A Future Leader in Search of an Issue

Back in 1989, the daughter of a former Baltimore Mayor had only barely won office, narrowly capturing a special election for a California congressional seat against the charismatic progressive successor to Harvey Milk, San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ Harry Britt. Britt had championed his career on combatting AIDS, whereas Pelosi had the political pedigree, but not a cause to be known for, according to The Nation. A rematch with Britt probably wouldn’t go so well for the California congresswoman.

Subscribe to Observer’s Politics Newsletter

Then, the tanks rolled in against pro-Democracy student protesters. And Pelosi had her issue.

“Congress quickly looked for ways to respond to the shock and horror that Tiananmen produced,” Richard C. Bush, chair of the Center for East Asia Policy Studies at the John L. Thornton China Center, wrote for the Brookings Institution. “It felt that the George H. W. Bush administration was too tepid in its response, and many members criticized the administration harshly. But Congress was constrained by its lack of leverage over executive branch policy and the conflict among U.S interests.”

Standing Up for Students

While most Americans gaped in horror at the slaughter, Pelosi got busy. Her priority was protecting the 40,000 Chinese students studying abroad in America. They had engaged in sympathetic demonstrations in America, and the Chinese secret police was taking pictures and notes here in the U.S. Threatening letters and pictures of family back in China were sent to these pro-democracy students. The message was crystal clear: It would not go well if they were sent home.

Pelosi probably thought her bill wouldn’t generate much disagreement. Who would stand with China after their barbarous breakup of the protesters? But she drew a powerful opponent in President George H. W. Bush. The GOP president didn’t want to lose diplomatic and economic ties with the People’s Republic of China. And he vetoed her bill, but signed an executive order agreeing with many of her points.

Pelosi also joined her colleagues in pushing for a ban on Chinese-made AK-47s to punish the People’s Liberation Army for their massacre. Though unsuccessful at the time, one could say it paved the way for a more far-reaching Assault Weapons Ban in 1994 that lasted a decade.

The matter might have ended there for most politicians, having “won the day.” But it became a cause célèbre for Pelosi. Two years later, on a congressional delegation to plead for the release of some Chinese dissidents, she ducked away from an organized museum tour, feigning a headache, to unfurl a banner stating, “To Those Who Died For Democracy In China,” right in front of the media, earning a sharp rebuke from the People’s Republic of China for her illegal action.

Continuing to Challenge China

Even after earning the House Speakership, Pelosi continued to antagonize the Chinese regime, meeting with pro-democracy dissidents during another diplomatic trip in 2009, after pushing for a boycott of the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

Pelosi’s had her share of critics over her China policy, and not just from Republicans. According to POLITICO, “UCLA political science professor Richard Baum, who advised Hillary Clinton on China during the 2008 presidential campaign, says Pelosi needed to moderate her image in China to remain relevant. ‘Nancy Pelosi, God bless her, has gotten off her high horse,’ he said. ‘It’s a question of what works. And humiliating them and making them lose face in public by shaming them doesn’t work. What does work is persistent, long-term quiet pressure.'”

Does it, though? During the slaughter at Tiananmen Square, I was a college student, who studied Chinese affairs while taking classes with Dr. John G. Stoessinger, a widely published political scientist who personally experienced much of what most professors write about. I was writing about whether to link human rights to trade. And we’ve seen, ever since, how ignoring political freedom can lead to consequences in economic freedom—in the form of Chinese tactics in dumping, pirating, hacking, currency manipulation and state subsidies.

Pelosi’s Surprising Anti-Communist Legacy

The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation is hosting a series of events in Washington, D.C., trying to call attention to the brutal events of June 4, 1989. Most associate anti-communism with conservatives like Richard Nixon, Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, as that was the case throughout much of the Cold War.

But whether you like Speaker Pelosi or not, you’ve got to appreciate her role in championing democracy and human rights in China, taking her own anti-communist stand and getting liberals on board with such policies, when presidents were more interested in free trade and business relationships with the People’s Republic of China.

Willingness to champion these Chinese students elevated Pelosi throughout the ranks of the Democratic Party, turning what could have been a short political career into America’s first female House Speaker.

John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Georgia—read his full bio here.